What % Of People Use The Meat From The Animals They Hunted

Abstract

Information technology is well known that wild game provides a significant proportion of the dietary poly peptide of the indigenous people of the eastern half of New Guinea (PNG), but almost zilch is known of its importance in the western half (the Indonesian province of Papua or Irian Jaya). We quantified hunting endeavour, harvest rates and wild meat consumption and sale in the Jayapura region of north-east Papua through interviews with 147 hunters from 21 villages and meal surveys in 93 households. Ten species of mammals, vii species of birds and at least two species of reptiles were harvested in our study area, but the introduced wild pig and rusa deer were the major target species. Hunting in our study area has shifted from a purely subsistence activity towards a more commercial grade at to the lowest degree partly due to the emergence of markets created past Indonesian transmigrants. Although the hunting of non-ethnic and certain native species might exist sustainable, the maintenance of populations of large threatened species volition require sensitive direction.

Introduction

Hunting by indigenous peoples is no longer sustainable in many tropical forest regions (Robinson and Redford 1991; Bennett and Dahaban 1995; Alvard et al. 1997; Robinson and Bennett 2000). Increased human population growth, improved hunting techniques, greater accessibility to forest interiors and increased economic benefits inevitably pb to increased hunting pressure and therefore local if non regional declines in wildlife populations (Bennett et al. 2000; Wilkie et al. 2000). In the vast tropical rainforests of New Republic of guinea, the world'south second largest island, the hunting of wildlife has traditionally been 1 of the most of import livelihood activities of indigenous people considering information technology provides well-nigh of a family's animate being poly peptide (Petocz 1989; Dwyer and Minnegal 1991; Sillitoe 2001; Mack and West 2005). Moreover, wildlife is of import culturally since various fauna parts are used equally adornments in ceremonies or as ornaments (e.thousand., feathers and fur) and tools (eastward.g., bones and teeth) in daily life (Majnep and Bulmer 1977; Frith and Beehler 1998). In addition, sure animals are part of the traditional belief systems of many ethnic groups (Majnep and Bulmer 1977, 2007; Kwapena 1984; Healey 1989, 1993).

Whilst in that location have been many studies of hunting in New Guinea (see Cuthbert 2010 for summary), most are from an anthropological perspective. Few have considered the sustainability of hunting practices, even so in the eastern one-half of the island (Papua-New Republic of guinea) lone, the number of wild vertebrate animals killed for domestic consumption is estimated to be between four and eight 1000000 (Mack and West 2005). New Guinea differs from other tropical rainforest regions of the world in having few large native game species, the largest existence the flightless cassowaries (Casuariidae; 25–60 kg). Equally these few large animals provide the highest protein reward, they are usually the first to be extirpated from forests close to villages (e.g., Male monarch and Nijboer 1994; BirdLife International 2000; Richards and Suryadi 2000). Indeed fossil evidence suggests that hunting has contributed to the local extinction of several species of larger mammals in New Guinea in the by (Flannery 1994).

Recent analyses of hunting and capture rates, combined with estimates of population densities and rates of increase, have shown that offtake rates of cassowaries and several often killed medium-sized mammals are unsustainable (Johnson et al. 2004; Cuthbert 2010). Not surprisingly, xi of the 14 species of tree-kangaroos (Dendrolagus spp.), nigh of them endemic to New Guinea, and 2 of the 3 cassowaries, are now considered threatened with, or vulnerable to, extinction, principally due to hunting (Stattersfield et al. 1998; IUCN 2010). To date, even so, studies of hunting practices in New Guinea take been largely confined to the eastern half of the island, where there is petty or no market for "bushmeat" or merchandise in wildlife (Mack and W 2005; Cuthbert 2010).

The Indonesian province of Papua (formerly Irian Jaya) covers the western one-half of New Guinea, and with a total country expanse of 416,129 kmii, is the nation'due south largest province. Although hunting of wildlife in Papua is not prohibited, the Republic of indonesia government has ratified laws for the protection of certain species of fauna (Government Regulation PP No. vii 1999). Virtually villagers are unaware of these regulations. Moreover, a lack of adequate monitoring and enforcement by the government, and the need to brand a livelihood and carry out traditional customs, local people however hunt and merchandise wildlife, including many 'protected' species, in both 'protected' and non-protected (Suryadi et al. 2007; Pangau-Adam and Noske 2010).

Profound social changes over the final ii decades (Timmer 2007) accept dramatically altered hunting pressure and marketplace demand for animal products in Papua. Rapid evolution and improved infrastructure accept enabled hunters from remote villages to offering their harvest in the markets, and increased numbers of vehicles have accelerated the send of harvested animals to marketplace towns. In improver immigrant communities of not-indigenous people, spawned by past Indonesian transmigration programmes, have created regional, national and fifty-fifty international markets for the exploitation of local natural resources. Hunting is thus gradually moving away from a purely subsistence towards a commercial course. Commercial harvesting of wildlife thus threatens the traditional life-styles of indigenous populations, through the weakening or loss of traditional laws and taboos (Kwapena 1984).

The aim of the electric current study was to expand our cognition of ethnic hunting practices in New Guinea by quantifying its extent amongst villagers in the Jayapura region of northeast Papua, Indonesia, where no such studies have been undertaken to date. We designed surveys to quantify hunting try and techniques, harvest rates of target species, and the motivations for hunting. Nosotros as well conducted meal surveys to make up one's mind the level of consumption of wild meat and other nutrient items, and monitored 2 local markets to measure the extent of bushmeat trade using these data. Nosotros consider whether current wild animals extraction rates might exist a crusade for concern in this function of New Guinea. As the hunting and trade of birds from these villages has been described elsewhere (Pangau-Adam and Noske 2010), this newspaper focuses on the exploitation of mammals and reptiles. Following Mack and W (2005) we use the terms 'wildmeat' and 'bushmeat' to distinguish between wildlife killed for consumption past the hunter and his family, and those that are killed to generate income, respectively.

Study Area and Methods

Our written report area was located about 110 km west of Jayapura, the capital city of Papua, Indonesia. Although forests around the villages had been cleared for agriculture, large principal wood areas remained. Roads and trails provided admission into the forest. At an peak ranging from 50 to 200 g to a higher place sea level, the vegetation of the study area was boiling (lowland) tropical rainforest subject to inundation (Conservation International CI 1999). Typical canopy tree genera were Ficus, Pometia, Intsia, Canarium, Alstonia and Terminalia, while understory trees included Myristica, Syzygium, Garcinia, Diospyros, Pandanus and palms, including rattans. Ethnically, most of the local people in this area belong to the Genyem group. They are divided into several clans, each of which owns one or more than woods blocks, every bit almost all land in Papua is claimed equally a state correct of a tribe.

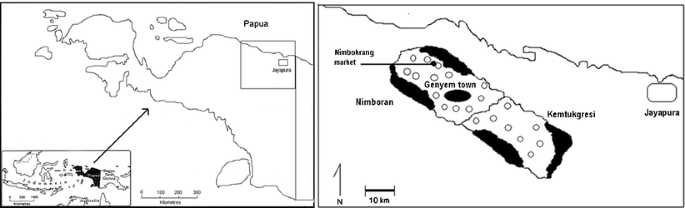

Surveys were conducted each calendar month from July 2005 to June 2006 at two woods sites in each of two districts (Nimboran and Kemtukgresi) of the Jayapura region (Fig. i). Nimboran district (660 km2) independent 14 villages, including two transmigration villages, with a total of 4,329 inhabitants, and included two areas of partly logged lowland rainforest on relatively flat land crossed by several roads fabricated by the loggers. These forests provided attainable bird watching sites for international bird watching groups. Kemtukgresi commune (625 kmtwo) had a similar population with 3,752 inhabitants living among 11 villages, but there was no transmigration hamlet, and the woods was in hilly terrain, used trivial by loggers or birdwatchers. Nimboran district besides supported the large trading town of Genyem, and well-nigh villages sampled in this district were closer (1–fifteen km) to this boondocks than those in Kemtukgresi district (10–xxx km) (Fig. 1). Nosotros predicted that the level of merchandise in game animals (bushmeat) would be higher in Nimboran villages due to their closer proximity to this trading town.

Map of Papua (left) and study sites in north-e Papua (right). Dots represent sample villages in Nimboran (n = xiii) and Kemtukgresi district. (n = 8); black areas represent wood sites (due north = ii in each district)

Hunting data were collected through interviews, structured questionnaires, and hunting surveys in 13 villages in Nimboran district, and eight villages in Kemtukgresi district. Village or customs leaders were first approached and interviewed to obtain general information on the number of households engaged in hunting practices. Semi-structured interviews were and so conducted with the hunters at their households or in c. 20 % of cases, on their way home from hunting sites. A total of 147 hunters (84 in Nimboran and 63 in Kemtukgresi) were interviewed using a set of questions designed to quantify hunting try and techniques, species harvest rates, and the motivations for hunting.

Each hunter was asked: (1) the duration of all hunting trips during the last month, (2) hunting group size, (3) altitude traveled to hunting sites, (4) types and number of weapons and/or traps used, (five) number and species of animals harvested in the last month, and (6) the intended use of captured animals (subsistence or commercial). Recently killed animals were weighed with standardized scales and identified using field guides (Beehler et al. 1986; Menzies 1991; Flannery 1995). Hunters were also asked about their perception of population trends among the most oftentimes targeted species. The annual off-take for each village was calculated by adding the monthly animal kills reported by hunters for the entire year. Wild meat off-accept by weight was calculated past multiplying the number of animals reportedly killed each year by the average body weight for each species concerned (sourced from Beehler et al. 1986; Menzies 1991; Flannery 1995).

Household repast surveys were conducted to determine the level of consumption of wild meat and other food items (i.e., livestock meat, fish, vegetables). These surveys consisted of interviews with housewives in 93 households amid four villages (n = 56) in Nimboran and three in Kemtukgresi (n = 37). Each housewife was asked about the kinds of meals they prepared during a i-calendar week period. All respondents identified themselves as belonging to the Genyem ethnic group.

In improver two local markets in Genyem and Nimbokrang were monitored each week to measure the regularity and extent of wildlife trade. Informal discussions were conducted with 33 vendors to identify the species being sold, their source, weight, price, and demand from buyers.

Results

All villagers consumed wild meat killed by hunters at least occasionally, especially at formalism events, and traditionally, each animal killed was shared past all family or clan members, or even all villagers, if the village was pocket-size. Yet but 15–20 % of villagers were actively involved in hunting. All hunters were male, ranging in age from 16 to 69 years old, and almost all village leaders were part-time hunters. Approximately sixty % of the 147 hunters interviewed identified themselves as professional hunters who as well farmed (56 % and 49 % in Nimboran and Kemtukgresi, respectively), as opposed to 37 % (xix % in Nimboran and 36.5 % in Kemtukgresi) who indicated that farming was their master profession and hunting a part-time activeness only. Full-time hunters were rarely encountered (iii %) in our study area. The stated reason for hunting was overwhelmingly for commercial gain. Only five % of hunters in Nimboran (including the market boondocks of Genyem), and 38 % of those in Kemtukgresi, alleged that they hunted primarily for subsistence.

Hunting Techniques

Several different hunting techniques were practised and each hunter typically used more than one technique. The nigh widely used techniques were snare trapping and archery (Table i). Foot snares rely on an animal falling into a modest concealed pit, which triggers the release of a bent sapling that causes a nylon or wire noose to grip tightly around the animate being's leg. Bush or wood materials were used to trap small marsupials (e.m., bandicoots) and ground-dwelling birds. Captured animals often suffer a painful decease, equally most animals struggle violently to gratuitous themselves, often breaking limbs and dying slowly of shock, claret loss, exhaustion and starvation. Animals occasionally escape past severing a human foot or by breaking the snare. Snares are nonselective with respect to species, age or sex of targeted animals, but they can be selective in regards to the size of an fauna. Large snares were set to capture wild pigs, rusa deer, cassowaries and wallabies, while smaller ones were set for trapping bandicoots, and large footing-dwelling birds such as Crowned Pigeons and megapodes (Megapodiidae). Some hunters checked their snare lines only twice a week, simply most checked them every other twenty-four hours. Hunters reported that wild pigs tin can survive up to a week in snares, but cassowaries could not survive more than 3 days.

Along with catapults, air rifles were used for killing or capturing flying foxes and arboreal marsupials, every bit well as birds of paradise. Hunting with dog and a spear was mainly used to catch White-striped Wallabies, wild pig and rusa deer. In both districts, some hunters too hunted at nighttime using flashlights and spears. Cuscuses and tree kangaroos were occasionally defenseless during the day by felling trees.

Hunting Practices

Hunting is generally practised lonely. Even so, when they need to hunt animals for community festivals and religious ceremonies, the members of a association group may hunt together. In our area, hunting sites corresponded to "clan forests", which included secondary woods and chief wood, as well as mixed gardens. A full of 26 and 18 hunting sites were identified in Nimboran and Kemtukgresi, respectively. Habitats used for hunting varied from mixed gardens near villages to the deep interior of primary woods.

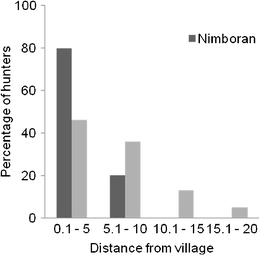

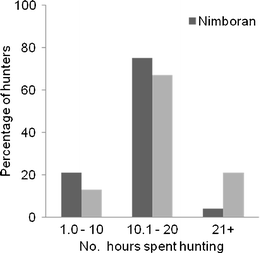

The altitude travelled from village to hunting sites ranged from 2 km to 16 km, and as expected, differed between the two districts. Hunters from villages in Kemtukgresi made more medium-distance hunting trips (5–ten km) than those from Nimboran (Fig. 2). The mean distances to hunting sites in Nimboran and Kemtukgresi was iv.4 km and seven.4 km, respectively, and the difference was significant (t = − vi,viii, df = 145, p < 0.01) (Fig. 2). Accordingly, the amount of fourth dimension devoted to hunting was significantly longer for hunters from Kemtukgresi than for those from Nimboran (t = 4.05, df = 73, p < 0.01), with an average (and maximum) of 19.6 (48) and 12.seven (35) hours per week, respectively, in these villages (Fig. 3). Several hunters mentioned that hunting activity decreased during the rainy season (October-Feb), because of low visibility, decreased animal activity during heavy rains, and reduced admission to sites due to flooded rivers. In villages with farms, some hunters turned to clearing, burning and planting during this fourth dimension of the twelvemonth.

Distances (in km) walked to hunting sites by hunters from ii districts in northeast Papua. No. hunters, 83 (Nimboran) and 63 (Kemtukgresi)

The amount of time (hrs) devoted to hunting by hunters from two districts in northeast Papua. No. hunters, 84 (Nimboran) and 63 (Kemtukgresi)

Target Animals

Of the 12 non-avian hunted taxa that were identified, ten were mammals and ii were reptiles (Table two). Five of the mammal species have putative 'protected' status nether Indonesian law for Natural Resources and Ecosystems (Government Regulation PP No. seven 1999). The introduced wild squealer and rusa deer were the most frequently killed mammals in both districts (estimated combined total of 1055 and 442 individuals, respectively), and due to their large size, comprised the bulk of the biomass of all harvested animals (75 % of estimated annual total of 87.nine tonnes) (Table two). The adjacent most often killed animals were ii species of bandicoots, but due to their small size, they comprised only a minor proportion of the total wild meat harvest. In contrast, the Northern Cassowary was the fifth well-nigh oft caught animal, all the same owing to its big size (60 kg), it constituted xx % of the estimated almanac total biomass (Pangau-Adam and Noske 2010). The remaining mammals, all marsupials, were killed much less oft, and included the Grizzled Tree-kangaroo (15.5 kg), White-striped Wallaby (5.5 kg) and three species of cuscuses (< 5 kg; Tabular array ii). Although snakes were rarely captured, the numbers of monitor lizards killed exceeded those of many mammal species (Table 2).

The number of rusa deer killed was significantly higher at Nimboran than at Kemtukgresi, just the converse was truthful of the number of flight foxes and cuscuses of iii species (χ² = 67.29, df = ii, p < 0.001). These differences appeared to be due to the number of hunters hunting each species, as there were no pregnant differences between the two districts in the number of each species killed past each hunter (Table 3). The number of animals killed per hunter annually varied greatly, ranging from half dozen to 48 animals (including birds) in Nimboran, and 3–53 animals in Kemtukgresi. Combining mean estimates of harvest rates from both districts (n = 147), an boilerplate of 20.1 animals (including birds) were killed past each hunter over 1 yr.

Market Analysis and Bushmeat Trade

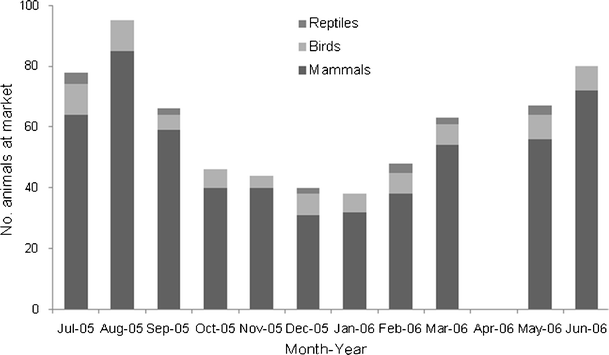

During the market place surveys, 33 vendors were found selling 7 mammal species and two reptile species (Table four). The number of animals being sold varied over the year, with significantly fewer animals during the wet season months of Oct to February (t = 5.19, df = 9, p < 0.001). The most ofttimes sold animals, year-round, were mammals (85 %) including wild pigs, rusa deer, flying foxes, bandicoots, cuscuses, wallabies and tree kangaroos, while birds and reptiles accounted for 12 % and three % of total animals sold, respectively (Fig. 4). According to 21 vendors, the bulk of consumers asked for the meat of placentals (grunter and deer), small marsupials (bandicoots and cuscus) and flying foxes. Monitor lizards (presumably mostly Varanus jobiensis) and big-bodied marsupials (tree-kangaroos and wallabies) were usually consumed by the hunters and their families or in the latter example, if however alive, reared as pets.

The number of wild fauna sold each week in Genyem and Nimbokrang markets, July 2005 to June 2006. Information technology was non possible to sample the markets in April 2006 due to civil unrest in the towns

Bushmeat was sold either fresh or smoked, and the cost ranged from US$two.twenty per animal for small mammals (viz. bandicoots and flight foxes) to US$50 for some large animals (rusa deer and wild pigs). Surprisingly, pythons fetched higher prices than kangaroos and wallabies (Table iv). Approximately 72 % of the animals offered for sale in the market place town (n = 587) were brought from the closest district (Nimboran), and the remaining 28 % from Kemtukgresi and other districts farther abroad. The meat of domesticated animals, such as beefiness and craven, was rarely offered for auction in the marketplace. Livestock dealers came from Jayapura city, and due to the long distance that animals would have to exist transported, they seldom participated in the meat trade in the Genyem region. The meat of domesticated pigs was found occasionally, but few villagers reared these animals for economic do good or every bit culling protein sources. This meat was more expensive than wild meat, considering domesticated animals had to be reared at significant cost to the household. Young cuscuses and tree kangaroos were besides captured to be reared every bit pets. However, if the possessor needed money, they sold these animals to the immigrant community or offered them in the markets.

Bushmeat was too occasionally sold directly within the villages. This was more common in villages located far from market boondocks, mainly those in Kemtukgresi district. If an animal was not sold rapidly within the hamlet, several hunters or their families would smoke the meat, then take it to the market over the following few days. In addition to meat, other animal products were sold, such as insect larvae, and turtle eggs. More than one-half of the respondents said that they shared bushmeat with relatives if it was non completely sold in the market or village.

Household Repast Analysis

Wild meat appeared to be the near prevalent source of animal protein in the seven villages sampled. From 546 records of meals, information technology was institute that the percentage of meals containing wild meat (51.1 %) was greater than those containing fish (17.4 %), domestic animals (thirteen.7 %), vegetables (sixteen.0 %) and/or other nutrient items (1.8 %). The composition of meals did not appear to differ betwixt the 2 districts just sample sizes were small (four villages in Nimboran and three in Kemtukgresi) for any statistical assay. Subsistence hunters hunted to satisfy the protein needs of their families, while commercial hunters captured and sold wild fauna for cash. Nonetheless, heads, legs and intestines of killed animals were typically removed (~1–5 kg per animal) for family consumption prior to transporting the prime meat cuts to the market or selling it in the village.

Word

Traditionally, hunting was an extremely important livelihood action in northeast Papua because information technology provided the majority of animal protein for families. Prior to western contact, Genyem people would take hunted only for subsistence purposes. The introduction of a cash market place economy, combined with rapid urban and infrastructure evolution in northeast Papua and transmigration programmes, still, have brought a pregnant change in hunting purposes and practices in this region. In our study, just 26 % of interviewed hunters declared that they hunted mainly for subsistence purposes, showing that there has been a marked shift from local-level subsistence hunting for meat consumption towards more than intensive commercial hunting. Consequently, Genyem people at present view wildlife equally a significant source of income. Family heads oftentimes viewed hunting every bit a style to fulfil their family's livelihood needs and to provide the financial back up needed for sending their children to schoolhouse. Although most hunters also grew crops, hunting was viewed as a way to obtain immediate greenbacks throughout the year, as opposed to the perhaps higher but merely seasonal economical benefits from agronomics.

Mack and Due west (2005) contrast the use of game as "bushmeat", where in that location is a market for this meat and merchandise items, with hunting in Papua-New Guinea, where at that place is little or no such market, and where the animals are used mainly as a source of "wildmeat.". Using their criteria, however, the use of game at our study sites in northeast Papua qualifies as "bushmeat", rather than "wildmeat (Table five). Commercial hunters invariably sold the valuable parts of harvested animals, but consumed the less valuable parts within their families. Drivers of demand also included requirements for ceremonial events. Thus the rationale for hunting past Genyem people, and likely other ethnic groups in Papua, differs dramatically from that reported in Papua-New Guinea to engagement.

At a central level these differences reflect the vastly unlike political and social development of the two sides of the island since the transfer of former Irian Jaya from one colonial power (Netherlands) to another (Indonesia) during the 1960s (Timmer 2007), and of PNG from Australian territory to cocky-government in 1975. In the case of Papua, President Suharto's 'New Society' led to the emergence of a well-established cash economy in which industries such every bit logging and plantation agriculture (oil palm, cocoa) provide employment for many transmigrants but only a pocket-size number of indigenous people (Boissière and Purwanto 2007). This economy has also led to a rampant and ongoing illegal trade in live birds although the participants are largely Indonesian transmigrants and few indigenous hunters are involved (Pangau-Adam and Noske 2010).

Hunting Methods and Practices

In our report, hunting with bow-and-pointer and trapping with snares were the predominant hunting techniques, both used in over seventy % of hunts. Bow and arrows are the traditional method of killing game throughout New Guinea (e.g., Majnep and Bulmer 1977). In the Crater Mountain Wild fauna Management Area (CMWMA) of the Eastern Highlands of Papua-New Republic of guinea, most a half of the kills were made with bow and arrows, whereas a relatively pocket-size proportion (c. 10 %) of kills involved the apply of traps (Mack and West 2005). The greater use of traps in Papua may be due to influence of transmigrants who introduced the utilise of cablevision snares, as well as the larger prey targeted. Snare trapping can result in high rates of wasted captures (Lee 2000; Noss 2000). In our study region, most hunters were well aware of how long animals could survive in a snare, yet many animals even so died in snares long before the hunter arrived considering hunters did non patrol snare lines on a daily ground. Air rifles were introduced to the trading boondocks by transmigrants from Java and S Sulawesi. Both local people and transmigrant settlers utilize this weapon to hunt Birds of Paradise, stuffed specimens of which fetch a like price to wild pig and deer meat. Due to the high price of air rifles and cartridges, however, relatively few hunters used this method of hunting.

The fact that hunters in Kemtukgresi hunted for longer and travelled further than those in Nimboran may be related to the lack of logging activities in Kemtukgresi district, as logging roads in the former district probably provided gear up access to more sites within 5 km of the villages. Despite marked disparities between our study surface area and CMWMA in homo population densities (vi.0–vi.vi persons per km2 and 1.8 km2, respectively), and ecosystem multifariousness, the hateful distances travelled past hunters are remarkably similar (1.vi–5.5 km in CMWMA, Mack and West 2005; four.4–7.4 km in Nimboran and Kemtukgresi, respectively).

Factors Influencing Target Species and Hunting Pressure level

The main hunting targets in this study were the introduced wild hog and rusa deer, apparently because of the large amount of meat each private provided. Although archaeologists have speculated that the wild pig has been in Papua for half-dozen,000 to 12,000 years, it seems likely that they arrived nigh 3,600 years BP (Diamond 1997), and they are now widespread throughout the island. The rusa deer, on the other manus, was introduced from Java only equally recently as 1928 and its known range is restricted to the southward coastal plains (Trans-Fly region), also every bit northwest and northeast Papua (Flannery 1995; Pattiselanno and Arobaya 2009). The availability of rusa deer in the study area, therefore, constitutes another important divergence betwixt this study and previous studies of hunting practices, all of which emanate from PNG. Also, in the contiguous areas of Wasur National Park, southeast Papua, and Tonda Wildlife Management Surface area, south-western PNG, where the rusa deer is causing big-calibration damage to swamps and grasslands (Bowe et al. 2007) there is widespread deer poaching to provide meat for the nearby township of Merauke, on the Papuan side of the edge, whereas on the PNG side the deer are not utilized by the local population autonomously from some trophy hunting (Bowe 2000; Stronach 2000).

In the CMWMA of PNG, large animals comprised a slightly lower percentage (58 %) of the total biomass harvested past hunters than in the present study (75 %), wild pig making the greatest contribution (31 %) and cassowary the rest (27 %) (Mack and West 2005). The most frequently killed animals in CMWMA were small-scale birds, cuscus and bandicoots, which comprisied twenty %, 16 % and xi % of all individuals, respectively, although only cuscus made a significant contribution (xv %) to the total biomass of prey harvested (Mack and W 2005). Data from this and 8 other hunting studies indicated that amidst medium-sized mammals, cuscus and bandicoots were the major source of game throughout PNG, accounting for 42 % and 26 % of captures, respectively, although the proportions of these 2 taxa were strongly negatively correlated, suggesting that they replaced each other equally the principal game in unlike areas (Cuthbert 2010). However there was no evidence of this effect amongst the two districts we studied in northeast Papua, with the estimated annual harvest of bandicoots existence 5–8 times higher than that of cuscus (Table two).

Hunting pressure level on a given targeted species in northeast Papua appears to be a function of ecological, cultural and economic factors. Of import ecological factors are the habitat preferences, behaviour and reproductive rates of the animals. Most of the primarily hunted species are habitat generalists. Wild pigs, flight foxes and bandicoots are known to survive in a range of habitats, including highly disturbed ones (Petocz 1994; Flannery 1995). As shown in other studies (Bodmer 1994; Robinson and Bennett 2000), differences in harvest rates between species in this study probably partly reflect the ease with which different species can be captured. Rusa deer and wild pig are relatively easy to hunt because they go out articulate trails in the forest along which snares can be prepare. Bandicoots are among the near ofttimes killed animals because they are abundant in secondary wood and mixed gardens adjacent to and fifty-fifty inside villages, and their trails are like shooting fish in a barrel to recognize.

Religious and cultural factors also influence hunting practices among Genyem people. For example, traditionally certain animals could be only hunted by the clan leaders, while others could non exist killed by hunters at certain times (e.chiliad. when their wives were pregnant). However there is some show that traditional Genyem behavior are breaking down equally some species that were once considered taboo (e.g. cassowaries, sure birds-of-paradise), are now hunted (Pangau-Adam and Noske 2010). Wildlife, mainly pigs, are still occasionally killed for community festivals and religious ceremonies. To provide sufficient wildmeat for such events, clans hunted as a group. When a large amount of meat is required for a cultural consequence, wildmeat is the near accessible source in rural areas (Pattiselanno 2006). Both wild and domesticated pigs play an important role for culture and traditional economies in New Republic of guinea (Majnep and Bulmer 1977; Flannery 1995), and are a major source of wildmeat for traditional Southeast Asian peoples (Alvard 2000; Bennett et al. 2000). In this report many hunters (91 %) also targeted wild pigs because the number of sus scrofa jaws they collected was traditionally a sign of their social condition.

The Importance of Commercial Hunting in North-Due east Papua

We believe that the critical gene explaining target species preferences in our study expanse is the anticipated economic benefits. The almost targeted species for commercial hunting were the largest-bodied (viz. wild pigs, rusa deer and cassowaries; all > xxx kg), as these animals provided more meat for sale and generated more economical benefits for hunters' households. The anticipated fiscal proceeds for a hunter from the sale of three such animals (US$35–l each) is approximately equivalent to the monthly salary of a locally employed permanent worker. High harvest rates of big-bodied diurnal animals have been reported from studies in other tropical forests (Colell et al. 1994; Bodmer 1994). In this study, differences in harvest rates of target species also appear to be influenced past marketplace need and consumer preferences for particular bushmeat. The meat of rusa deer, for example, was preferred past transmigrants over the meat of tree-kangaroos and wallabies, which was preferred by local people, according to interviewed hunters and market vendors. That more rusa deer were killed in Nimboran than Kemtukgresi appears to be due to a greater number of hunters hunting this species in the one-time commune, probably because of their popularity as bushmeat. In contrast, cuscuses and flight foxes were killed past fewer hunters in Nimboran than in Kemtukgresi possibly because they were less popular every bit bushmeat.

Several lines of testify support our prediction that the extent to which villagers engaged in commercial bushmeat merchandise is related to the altitude of their villages from the major market place. At Genyem market town, 72 % of the animals offered for sale had been brought from villages in the closest commune (Nimboran), and the residue from Kemtukgresi and other districts farther away. Although a similar percentage of hunters in the two districts considered themselves professional hunters, simply v % of hunters in Nimboran district declared that they hunted primarily for subsistence, equally compared to 38 % of hunters in Kemtukgresi.

Lack of alternative economical opportunities may be a driving forcefulness for the commercial hunting reported in this study. There are crop farming systems and pocket-sized-scale cocoa plantations in the region, just villagers seem less successful in pursuing this activity than the transmigrants, due to their lack of requisite cognition and skills (see for example, Timmer 2007). Logging companies also announced to prefer to employ non-indigenous peoples. Although many hunters were engaged in subsistence farming of maize, manioc, sweet potatoes and other vegetables, they felt that hunting could provide them with higher economic benefits. Since the market place in Genyem boondocks adult and is offering wild meat for sale three times per week, hunters have increased their efforts to harvest more wild animals in order to increase their profits.

Conservation and Sustainable Utilisation of Hunted Species

Despite the high hunting pressure on bandicoots in our study, hunters claimed that populations of these animals remained stable. This suggests that these animals have high reproductive rates, consistent with the ability of females to heighten large litters of upwardly to 9 pouch young twelvemonth-round (Flannery 1995). Indeed Cuthbert (2010) concluded that bandicoots (and ringtail possums) were the only grouping of medium-sized mammals that could provide a sustainable harvest in PNG, because of their loftier population densities, and high intrinsic rate of increase.

Withal most harvested fauna species in the study surface area are endemic to New Guinea, and three of the target species (Grizzled Tree-kangaroo, Northern Cassowary and Victoria Crowned Dove) are classified as Vulnerable past IUCN (2010). Although five of the ten mammal species targeted past hunters in our study area are theoretically protected by Indonesian law (Table 2), near 90 % of the interviewed hunters and villagers claimed that they were unaware of any legislation governing the protection of wild animals. Given this lack of local awareness well-nigh wildlife legislation, the lack of enforcement of laws pertaining to hunting and wild fauna trade, and the obvious involvement of Indonesian transmigrants and the military in the latter (Frazier 2007), it is inappreciably surprising that hunting of 'protected' animals continues among ethnic peoples.

A comparison of the reported rates of harvesting and estimated rates of production in Papua-New Guinea indicated that tree-kangaroos and cuscus are harvested unsustainably, whereas the hunting of bandicoots was lower than production levels, suggesting that bandicoots could potentially provide a sustainable source of poly peptide, in preference to scarcer and slower-convenance larger species (Cuthbert 2010). Alternatively, ongoing depletion of the latter species may create a substantial financial burden in areas where people accept the least nutritious diets and the poorest health intendance (Mack and West 2005).

Since hunting is crucial for Genyem people to run across their livelihood and customary needs, we advise a socially sensitive approach to wildlife management rather than a ban on hunting. In order to effectively manage hunting, it is useful to distinguish between the relative significance of hunting for subsistence and commercial merchandise (Rao et al. 2005). A number of wild animals such every bit tree-kangaroos, wallabies and reptiles in the Genyem area are only harvested to supply poly peptide for local people. To maintain wild populations of these and other economically or culturally valuable animal species, such as cassowaries and cuscuses, hunters ought to exist encouraged to hunt not-ethnic species (i.e., wild pig and rusa deer) that accept a negative bear on on natural habitats, and/or native species that take high reproductive rates, such as the bandicoots (Bodmer 1994; Fitzgibbon et al. 1995; Cuthbert 2010). Education programmes are essential to raise sensation about maintaining populations of threatened species among both local communities and regime, at both local and regional levels (Riley 2002). In addition, domesticated pigs could exist advocated as an alternative source of poly peptide with government back up for establishing pig farms. Whilst culling sources of income, such equally farming greenbacks crops (eastward.chiliad. cocoa and coffee), may reduce hunting pressure level on wild fauna, such activities could as well result in increased habitat devastation through the clearing of forests to allow planting of such crops.

References

-

Alvard, M. (2000). The impact of traditional subsistence hunting and trapping on prey populations: Data from Wana Horticulturalists of upland Central Sulawesi, Indonesia. In Robinson, J. G., and Bennett, East. L. (eds.), Hunting for Sustainability in Tropical Rainforests. Columbia University Press, New York, pp. 214–230.

-

Alvard, Thou. S., Robinson, J. G., Redford, K. H., and Kaplan, H. (1997). The Sustainability of Subsistence Hunting in the Neotropics. Conservation Biology eleven: 977–982.

-

Beehler, B. 1000., Pratt, T. K., and Zimmerman, D. A. (1986). Birds of New Republic of guinea. Princeton University Printing, Princeton, United states.

-

Bennett, E. 50., and Dahaban, Z. (1995). Wildlife responses to disturbance in Sarawak and their implication for woods management. In Primack, R. B., and Lovejoy, T. E. (eds.), Ecology, Conservation and Management of Southeast Asian Rainforest. Yale University Printing, London, pp. 66–86.

-

Bennett, Due east. L., Nyaoi, A. J., and Sompud, J. (2000). Saving Borneo's bacon: the sustainability of hunting in Sarawak and Sabah. In Robinson, J. K., and Bennett, Due east. L. (eds.), Hunting for Sustainability in Tropical Rainforests. Columbia Academy Printing, New York, U.s., pp. 305–324.

-

Birdlife International (2000). Threatened Birds of the World. BirdLife International, Cambridge, Britain.

-

Bodmer, R. East. (1994). Managing wildlife with local communities in the Peruvian Amazon: The case of the Reserva Comunal Tamshiyacu-Tahuayo. In Western, D., Wright, R. M., and Strum, S. (eds.), Natural Connections. Isle Printing, Washington DC., Us, pp. 113–134.

-

Boissière, M., and Purwanto, Y. (2007). The agricultural systems of Papua. In Marshall, A. J., and Beehler, B. M. (eds.), The Ecology of Papua, Part Ii. The Ecology of Indonesia Serial, Vol. Half-dozen. Periplus Editions, Singapore, pp. 1125–1148.

-

Bowe, 1000. (2000). Development of regional synergies between Northern Australia and the Trans-Fly region of Indonesia and Papua New Republic of guinea. In Russell-Smith, J., Hill, Chiliad., Djoeroemana, Due south., and Myers, B. (eds.), Burn and Sustainable Agronomical and Forestry Development in Eastern Indonesia and Northern Australia. Proceedings of an international workshop held at Northern Territory Academy, Darwin, Commonwealth of australia, 13–15 April 1999. Australian Center for International Agricultural Research, Canberra, Human action, pp. 138–142.

-

Bowe, M., Stronach, G., and Bartalo, R. (2007). Grassland and savanna ecosystems of the Trans-Fly, southern Papua. In Marshall, A. J., and Beehler, B. K. (eds.), The Environmental of Papua, Part Two. The Ecology of Republic of indonesia Series, Vol. VI. Periplus Editions, Singapore, pp. 1054–1063.

-

Colell, One thousand., Maté, C., and Fa, J. E. (1994). Hunting Amidst Moka Bubis in Bioko: Dynamics of Faunal Exploitation at the Hamlet Level. Biodiversity and Conservation 3: 939–950.

-

Conservation International (CI). (1999). The Irian Jaya biodiversity conservation priority-setting workshop', Biak, seven –12 Jan 1997. Final Study, Washington, D.C., USA.

-

Cuthbert, R. (2010). Sustainability of Hunting, Population Densities, Intrinsic Rates of Increment and Conservation of Papua New Guinean Mammals: A Quantitative Review. Biological Conservation doi:ten.1016/j.biocon.2010.04.005.

-

Diamond, J. Chiliad. (1997). Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. W.Westward. Norton & Company, New York, London.

-

Dwyer, P. D., and Minnegal, M. (1991). Hunting in Lowland, Tropical Rain Forest: Towards a Model of Non-agricultural Subsistence'. Human Environmental 19: 187–212.

-

Fitzgibbon, C. D., Mogaka, H., and Fanshawe, J. H. (1995). Subsistence Hunting in Arabuko-Sokoke Forest, Kenya and its Furnishings on Mammal Populations. Conservation Biology nine: 1116–1126.

-

Flannery, T. F. (1994). The Fossil Land Mammal Record of New Republic of guinea: A Review. Science in New Republic of guinea 20: 39–48.

-

Flannery, T. F. (1995). Mammals of New Republic of guinea. Reed Books, Commonwealth of australia.

-

Frazier, S. (2007). Threats to biodiversity. In Marshall, A. J., and Beehler, B. M. (eds.), The Ecology of Papua, Part 2. The Ecology of Republic of indonesia Serial, Vol. Six. Periplus Editions, Singapore, pp. 1199–1229.

-

Frith, C. B., and Beehler, B. M. (1998). The Birds of Paradise. Oxford Academy Press, Oxford.

-

Healey, C. (1989). The Man Who Became a Bird of Paradise: Myth in the Papua New Guinea Highlands. Northern Perspective 12: 24–30.

-

Healey, C. (1993). Folk Taxonomy and Mythology of Birds of Paradise in the New Guinea Highlands. Ethnology 32: 19–34.

-

IUCN. (2010). IUCN Red Listing of Threatened Species. Version 2010.4. [online] URL: http://www.iucnredlist.org. Downloaded on 30 April 2011.

-

Johnson, A., Bino, R., and Igag, P. (2004). A Preliminary Evaluation of the Sustainability of Cassowary (Aves: Casuariidae) Capture and Trade in Papua New Republic of guinea. Animal Conservation 7: 129–137.

-

King, C. E., and Nijboer, J. (1994). Conservation Considerations for Crowned Pigeon, GENUS GOURA. Oryx 28: 22–30.

-

Kwapena, N. (1984). Traditional Conservation and Utilization of Wild animals in Papua New Republic of guinea. The Environmentalist four: 22–26.

-

Lee, R. J. (2000). Impact of subsistence hunting in North Sulawesi, Indonesia and conservation options. In Robinson, J. G., and Bennett, East. L. (eds.), Hunting for Sustainability in Tropical Rainforest. Columbia University Printing, New York, pp. 455–472.

-

Mack, A. L., and West, P. (2005). Ten thousand tonnes of small animals: wildlife consumption in Papua New Republic of guinea, a vital resources in demand of management. Resources Direction in Asia-Pacific Working Paper No. 61. Resource Management in Asia-Pacific Program, Inquiry Schoolhouse of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University, Canberra.

-

Majnep, I. Southward., and Bulmer, R. (1977). Birds of my Kalam Country. Aukland University Printing, Aukland.

-

Majnep, I. S., and Bulmer, R. (2007). Animals the Ancestors Hunted: An Account of the Wildlife of the Kalam Area. Crawford House Publishing, Adelaide, Commonwealth of australia, Papua New Republic of guinea.

-

Menzies, J. (1991). A Handbook of New Guinea Marsupials & Monotremes. Kristen Pres Inc Madang, PNG.

-

Noss, A. (2000). Cable snares and nets in the Central African Republic. In Robinson, J. G., and Bennett, E. Fifty. (eds.), Hunting for Sustainability in Tropical Rainforests. Columbia Academy Press, New York, pp. 455–472.

-

Pangau-Adam, Yard., and Noske, R. A. (2010). Wildlife hunting and bird trade in due north-due east Papua (Irian Jaya), Indonesia. In Tidemann, S., Gosler, A., and Gosford, R. (eds.), Ethno-Ornithology: Birds, Indigenous Peoples, Civilisation and Society. Earthscan, London, pp. 73–86.

-

Pattiselanno, F. (2006). The Wild animals Hunting in Papua, Indonesia. Biota eleven: 59–61.

-

Pattiselanno, F., and Arobaya, S. Y. Due south. (2009). Grazing Habitat of the Rusa Deer (Cervus timorensis) in the Upland Kebar, Manokwari. Biodiversitas ten: 134–138.

-

Petocz, R. (1989). Conservation and Development in Irian Jaya. E.J. Brill. Leiden Princeton University Press, New Jersey.

-

Petocz, R. (1994). Mamalia Darat Irian Jaya (Terrestrial Mammals of Irian Jaya). Gramedia Pustaka Utama, Dki jakarta, Republic of indonesia.

-

Rao, M., Myint, T., Zaw, T., and Htun, S. (2005). Hunting Patterns in Tropical Forests Adjoining the Hkakaborazi National Park, Due north Myanmar. Oryx 39: 292–300.

-

Richards, S. J., and Suryadi, S. (2000). A Biodiversity Cess of Yongsu – Cyclop Mountains and the Southern Mamberamo bowl, Papua. RAP Bulletin of Biological Assessment 25. Conservation International, Washington DC.

-

Riley, J. (2002). Mammals on the Sangihe and Talaud Islands, Indonesia, and the Touch on of Hunting and Habitat Loss. Oryx 36: 288–296.

-

Robinson, J. G., and Bennett, Due east. L. (2000). Conveying capacity limits to sustainable hunting in tropical forests. In Robinson, J. Thousand., and Bennett, E. L. (eds.), Hunting for Sustainability in Tropical Rainforests. Columbia University Press, New York, pp. xiii–30.

-

Robinson, J. K., and Redford, Chiliad. H. (1991). Sustainable Harvest of Neotropical Wood Mammals. In Robinson, J. G., and Redford, K. H. (eds.), Neotropical Wildlife Employ and Conservation. University of Chicago Printing, Chicago, pp. 415–429.

-

Sillitoe, P. (2001). Hunting for Conservation in Papua-New Republic of guinea Highlands. Ethnos 66: 365–393.

-

Stattersfield, A. J., Crosby, N. J., Long, A. Yard., and Wege, C. (1998). Endemic Bird Areas of the World. Priority Areas for Biodiversity Conservation. Birdlife Conservation Series no. 7. Birdlife International, Cambridge.

-

Stronach, N. (2000). Fire in the Trans-Wing savanna, Irian Jaya/PNG. In Russell-Smith, J., Hill, G., Djoeroema, S., and Myers, B. (eds.), Fire and Sustainable Agricultural and Forestry Development in Eastern Indonesia and Northern Australia. Proceedings of an international workshop held at Northern Territory Academy, Darwin, Australia, xiii–15 April 1999. Australian Centre for International Agronomical Enquiry, Canberra, Human action, pp. 90–93.

-

Suryadi, A., Wijayanto, A., and Cannon, J. B. (2007). Conservation Laws, regulations, and legislation in Republic of indonesia, with special reference to Papua. In Marshall, A. J., and Beehler, B. 1000. (eds.), The Ecology of Papua, Function Two. The Ecology of Indonesia Series, Vol. Vi. Periplus Editions, Singapore, pp. 1276–1310.

-

Timmer, J. (2007). A brief social and political history of Papua, 1962–2005. In Marshall, A. J., and Beehler, B. M. (eds.), The Ecology of Papua, Part Two. The Environmental of Indonesia Series, Vol. 6. Periplus Editions, Singapore, pp. 1098–1124.

-

Wilkie, D., Shaw, E., Rotberg, F., Morelli, 1000., and Auzel, P. (2000). Roads, Evolution, and Conservation in the Congo Bowl. Conservation Biological science 14: 1614–1622.

Acknowledgements

Nosotros are grateful to the Genyem communities and district leaders for their support of this research. The Wildlife Conservation Society and Rufford Foundation provided fiscal support, without which this research would non have been possible. Many thanks to Supeni Sufaati, Katrin Mahuse, Elias Buiney and Pak Trip the light fantastic toe for assistance in the field and sincere cheers to Christos Astaras for the helpful comments on drafts of this commodity.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution License which permits any employ, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original writer(s) and the source are credited.

Writer information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Eatables Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted employ, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this article

Pangau-Adam, One thousand., Noske, R. & Muehlenberg, 1000. Wildmeat or Bushmeat? Subsistence Hunting and Commercial Harvesting in Papua (West New Guinea), Indonesia. Hum Ecol 40, 611–621 (2012). https://doi.org/x.1007/s10745-012-9492-5

-

Published:

-

Upshot Appointment:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-012-9492-5

Keywords

- Wildmeat

- Bushmeat

- Rusa deer

- Sustainable hunting

- Tropical forests

- Threatened species

- Irian Jaya

- Papua Indonesia

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10745-012-9492-5

Posted by: winklerwhadminvabot.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What % Of People Use The Meat From The Animals They Hunted"

Post a Comment